- 1. Welcome to a virtual (imaginary) tour guided by a local

- 2.Quick Overview! ”Shirakawa-go?”

- 3.Gassho-zukuri/prayer-hands style (Outline)

- 4 Gassho-zukuri houses open to public

- 5. Irori/Sunken hearth

- 6 Gassho-zukuri ground floor (living space)

- 7 Gassho-style attic (as work space)

- 8 Gassho-zukuri Attic (As architectural space)

- 9 Gassho-zukuri Attic (Remnants of Silkworm Farming)

- 10 Castle Ruins & Observatory

- 11 History of Gassho-Zukuri (Village People’s Story)

1. Welcome to a virtual (imaginary) tour guided by a local

Since this is a fairly long tour, it is strongly recommended that you join only one part of this tour only when you want a change of pace. I hope you don’t let this be a long and wrong tour❤

This blog delves into Shirakawa-go, a World Heritage Site, preserving the atmosphere of a village from Japan’s Edo(Samurai warriors)Period. Unlike official sites that provide detailed and sophisticated introductory information, this blog takes on the form of a virtual (imaginary) tour guided by a local. It addresses common questions that arise during a visit to Shirakawa-go, presenting each exhibit in a straightforward and engaging manner, making it easy to understand and interesting.

👉Note: If you’re seeking a detailed and sophisticated explanation, please refer to the official website or the websites of travel agencies.

For foreign visitors, business guests, and students exploring Japan, we extend an invitation to experience these stories firsthand. Come and witness the allure of Shirakawa-go in person! We will be waiting for you!

2.Quick Overview! ”Shirakawa-go?”

”About Shirakawa-go”

2.1 Basic Information

Let me start with a brief explanation of Shirakawa-go before you enter.

- It is a small farming village with about one hundred houses scattered over a one-kilometer stretch in a narrow crescent-shaped basin along a mountain river.

- This charming village is nestled in a mountainous region known for heavy snowfall and is renowned for its unique gassho-zukuri houses

- The houses feature steeply pitched thatched roofs designed to withstand heavy snowfall.

- These traditional houses date back to the 17th century, and centuries of enduring harsh winters have led to their remarkably efficient and rational design

- Shirakawa-go, along with the nearby village of Gokayama, is registered as a UNESCO World Heritage site, showcasing its picturesque setting and traditional way of life.

- Since becoming a World Heritage site about 30 years ago, the small village has attracted around 2 million tourists annually, both from domestic and overseas.

- With the view of a cluster of gassho-zukuri houses, all aligned with their fronts facing the same direction, you might feel as if they were alive, looking down on you.

- Although there are gassho-zukuri houses in other areas, the people here continue to live in an environment that has remained unchanged for hundreds of years, with sustainability being highly valued.

- It’s a representative success story of a small local government that has successfully transformed itself from relying on former financial sources, such as the sericulture industry, to a thriving tourism business model.

- The changing colors of seasonal flowers, autumn leaves, and snow, along with nighttime illuminations, can be enjoyed as a tranquil form of nature’s projection mapping.

2.2 Ready to Crack a Smile? Short Stories for You!

Here are short stories addressing common questions from foreign visitors like you who are interested in learning about Japanese culture and local people. I hope you enjoy some of them!

Q1 “How did such a village come to be?

- Originally, it is said that there were quite a few other villages in Japan with houses like these.

- The design concept for buildings such as the gassho-zukuri was to adapt them to the harsh natural environment.

- This sharply sloped roof was designed to prevent heavy winter snow from accumulating.

- Additionally, due to the scarcity of farmland, a large work area on the second floor and in the attic was necessary for keeping silkworms and generating income from sericulture.

- Since many villages in Japan were situated in similar natural environments, houses like gassho-zukuri were likely not so rare.

- In the modern era, however, sericulture became an unviable source of income, leading to the abandonment of many gassho-zukuri houses and the departure of residents from the villages.

- What was unique here was that they managed to stave off destruction and dispersion just in time.

- Among patient farmers, the people here might have been exceptionally so.

- It is said that the ancestors of this community were defeated in a power struggle long ago and were driven out of the capital, eventually settling here much like hidden Christians.

- They had nowhere else to go, and despite the changing environment, they had no choice but to adapt and live here using their resourcefulness.

- Accidentally, I reflected on our human history of striving to conquer fertile lands and historically significant places by any means necessary.

- Perhaps what should be preserved as a true World Heritage site is not just the buildings here, but the DNA and spirit of the people of Shirakawa-go, who were determined never to invade others.

3.Gassho-zukuri/prayer-hands style (Outline)

3.1 Basic Information

- Although the Gassho style architecturally belongs to the A-frame, its concept was not born from aesthetic ideas but rather from the need to optimize the harsh natural environment.

- The steep roof angle was established over a long period of time to prevent the house from collapsing due to snow accumulation and to maximize the space available for sericultural work inside the building.

- ‘Gassho’ means to put one’s hands together in prayer, and it is said to derive from the mountain-like roof shape that reminds us of the deep piety of the people here.

- The roof is covered with several layers of locally harvested thatch, less than one meter thick, which provides excellent sound insulation and heat retention, offering warmth in winter and coolness in summer.

- The floors above the first floor for residential use are divided into multiple stories to maximize productivity for indoor work at night and in winter, and there are no partitions to ensure ample light and ventilation.

- The building is assembled with ropes, creating a flexible structure that disperses external pressure and is resistant to windstorms and earthquakes.

- A sunken hearth is placed on the first floor, and the smoke from it helps protect the building from pests and rot by fumigating the interior before exiting through the floor and thatched roof.

- Considering wind flow and sunlight on the roofs, the houses were built to face north-south and be aligned to avoid crowding.

- The thatching of roofs is replaced every 20 to 30 years by a group of village residents, a practice that is becoming rarer due to the decreasing population and the increasing reliance on specialized contractors.

- Nowadays, visitors can observe large annual fire drills, where water is discharged all at once, conducted due to the vulnerability of thatched roofs to fire, not for entertainment.

3.3 Ready to Crack a Smile? Short Stories for You!

Q1 “Why is it called gassho-zukuri?”

- Since Shirakawa-go became a World Heritage site, the term ‘gassho’ has gained international popularity and is recognized by many foreigners visiting Japan.

- It is also widely used in various translations, such as ‘prayer-hands style,’ ‘thatched-roof style,’ ‘steeply sloped roof style,’ and ‘A-frame,’ to describe its appearance.

- There are various theories about when the term came into use, but a common factor is that it derives from the Japanese expression for putting one’s hands together in prayer or gratitude.

- Indeed, the cross-section of the roof, assembled in a mountainous shape, resembles the profile of two hands together, but instead of being overlapped, it takes the form of a triangle similar to a pyramid.

- Ultimately, the naming reflects the deeply rooted religious beliefs and nature worship of the Japanese people.

- However, some technically oriented individuals may be concerned that the term ‘gassho’ does not accurately represent the actual shape of the structure.

- For example, it resembles an almost equilateral triangle, so it might be more accurately described as traditional truss architecture or a Japanese A-frame house.

- It might be more accurate to start with the Japanese mentality, as focusing solely on appearance can often be misleading.

- The term ‘gassho’ may not have been chosen for its shape but rather for the spiritual condition of people who, in their struggle to survive, had no choice but to pray with their palms together, asking for God’s help.

- Long ago, the early construction style was mediocre, but it evolved into this unique form through hundreds of years of prayerful aspiration.

- Furthermore, they might have put their hands together in gratitude, thanking God for their successful survival to this day.

- Coincidentally, ‘gassho’ in Japanese sounds like ‘God shows’ in English. How about using this new catchphrase?

- Gassho-zukuri: A Divine Solution for Survival! It Literally Shows Universal Architecture—’God’s Show’!

4 Gassho-zukuri houses open to public

4.1 Basic Information

- Shirakawa-go has a few gassho-zukuri farmhouses that are open to the public, many of which have been continuously used as residences since they were originally built.

- These open houses allow visitors to explore the unique, well-preserved architectural features and interior showcasing historical significance of the gassho-zukuri style from within.

- While all of them share common features of gassho-zukuri architecture designed to accommodate extended families in an environment with limited land, each house also has distinct structural elements tailored to its own purposes.

- In general, these houses needed to be large enough to accommodate multiple generations and relatives, as well as to provide ample space for sericulture work, which required round-the-clock attention, and for the servants involved.

- The Wada House is one of the largest houses, and since its owner was the head of the village, it has a formal entrance for receiving local government officials, though this entrance is usually closed except during special events such as festivals.

- This house, designated as an important cultural asset with a history of nearly 200 years, includes a storehouse and a rest room next to the house—making it unusual for a rest room to be registered as a historical asset.

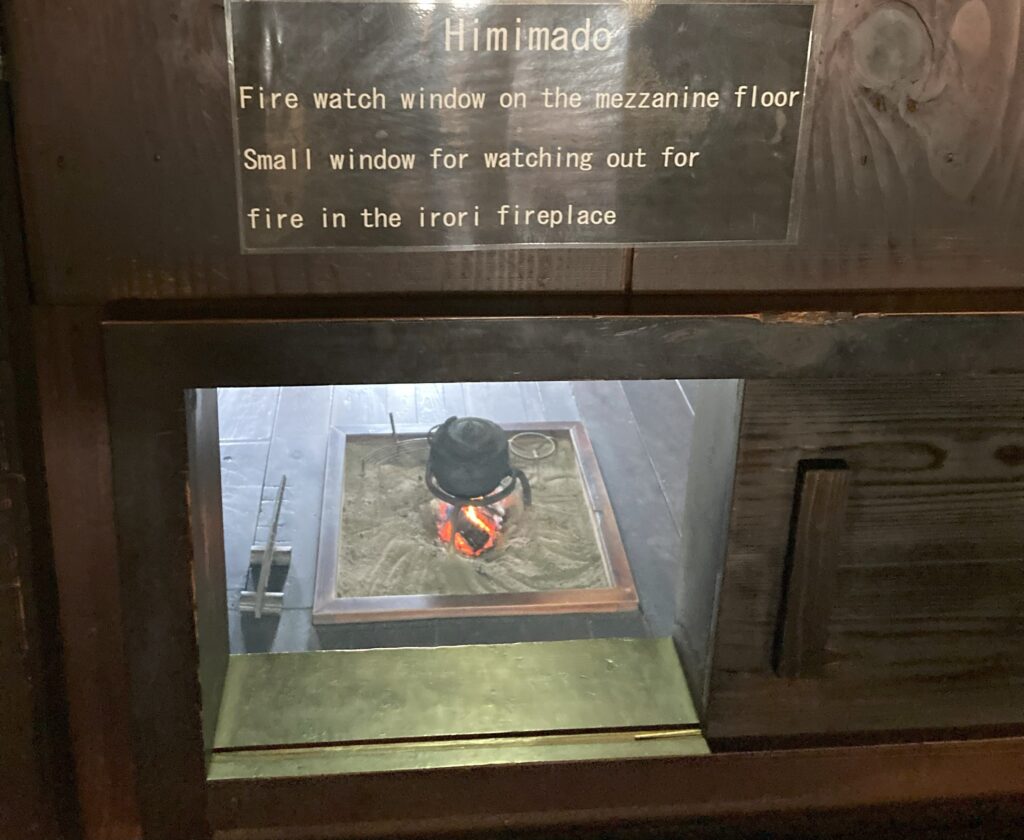

- Kanda House, a branch of Wada House, features a mezzanine floor with a small window for monitoring the fire in the hearth on the first floor, which is still used and remains continuously burning all day long.

- The Nagase family residence, historically used as a doctor’s home, is constructed from centuries-old natural cypress, horse chestnut, and zelkova, symbolizing the high status of the family.

- At Myozenji Temple, the storehouse and bell tower gate are also built in the gassho-zukuri style, creating a unique atmosphere reminiscent of religious assemblies, similar to churches, which is not found in ordinary houses.

- There is an exhibition area where over 20 gassho-zukuri houses, including a shrine and a water mill house, have been relocated, offering visitors a chance to experience the atmosphere of a whole farm village from that time, complete with carp swimming in the stream.

4.2 Ready to Crack a Smile? Short Stories for You!

Q1 “Is the interior of gassho-zukuri houses the same as the exterior?”

- Yes, gassho-zukuri is a sturdy construction method that reflects the architectural philosophy of Shirakawa-go, enhancing adaptability to the harsh natural environment.

- Furthermore, this concept was also aimed at increasing the productivity of sericulture, which provided a significant source of income in a village with limited farmland.

- The structure of each farmhouse was essentially the same inside and out, as meeting these requirements was crucial for survival.

- Of course, some houses have held important positions for generations or served as doctors’ homes, and their interiors and furnishings reflect their high status and income.

- Many day-trippers may be satisfied with just one house, but if you’re staying overnight and have more time, you can visit the others and appreciate the differences.

- Among them, the sericulture areas on the second floor and above are particularly surprising and satisfying to many visitors.

- The exposed post-and-beam framework was bound with ropes to make the building flexible, allowing it to withstand storms and earthquakes by dispersing external forces.

- Additionally, they have been slowly fumigated over many years in the smoke of a sunken hearth, giving them a slightly shiny black color and a unique luster, akin to artistic craftwork shaped by nature’s power.

- In addition, the construction, designed to maximize lighting and air circulation before the advent of electricity, creates a very open and relaxing atmosphere.

- With a folk art style table placed beside the window, the space could easily resemble a stylish and attractive coffee shop or restaurant without any modern business efforts.

- How could this area, originally designed to create an optimal environment for the delicate silkworms, not also be comfortable for humans?

- Since silkworms eat a lot of mulberry leaves to produce high-quality silk threads, serving mulberry leaf jam here could be a fitting addition.

- This imagery, such as the ‘Cocoon Restaurant’ where tourists from around the world enjoy the atmosphere and taste, makes me wish that they return home and share their experiences online.

- I hope they do so with the same enthusiasm as silkworms produce high-quality silk threads.

5. Irori/Sunken hearth

5.1 Basic Information

- Irori is a hearth commonly found in traditional Japanese houses, including gassho-zukuri, where the floor is recessed into a square or rectangular shape and wood or charcoal is burned on ashes placed at the bottom.

- Pots and kettles were hung from hooks suspended from the ceiling for cooking, while the hearth also served as a source of heating and lighting, making the sunken area a central gathering place for the family to enjoy together.

- Cooking was generally done using pots over the fire to prepare rice and stews, while fish and other ingredients were skewered and roasted over the ashes around the fire.

- The hearth was used to safely light the room without the risk of tipping over, making it a good place for small tasks such as repairing tools and sewing, especially in winter and at night.

- The fire in the sunken hearth was maintained at all times to avoid the burden of repeatedly making fire, as modern fire-starting devices like lighters and matches were not available at that time.

- Around the hearth, which served as a place for family gatherings and hosting guests, the family head sat at the center, closest to the hearth, while the women and children sat farther away.

- The most unique feature of Shirakawa-go’s hearth is its design, which ensures that smoke and heat are distributed throughout the gassho-zukuri building.

- In Shirakawa-go, the intentional lack of chimneys or large smoke openings allowed the houses to improve their durability by constantly fumigating the pillars, beams, and thatched roofs, which increased their resilience to insects and rot.

- To maintain the fire in the hearth stably and efficiently over a long period, the fuel wood was kept thick and not chopped into small pieces, allowing it to smolder slowly, except when intense heat was needed.

- A multi-purpose lattice shelf suspended directly above the hearth receives and diffuses smoke and heat while acting as a filter, causing it to glow black with soot and tar.

5.2 Ready to Crack a Smile? Short Stories for You!

Q1 “Do people cook here?”

- Yes, the pots were used for cooking over the fire, but they also served as lights in the days before electricity, when only candles were available.

- But besides these uses, the hearth also performs other crucial functions that enhance the building’s durability.

- The heat and smoke from this fire escape through the cracks in the ceiling and eventually through the floor above and the thatched roof.

- This fumigation helps to prevent harmful insects and wood rot from damaging the building.

- Therefore, to maximize the benefits of this hearth fire, it was kept burning continuously, which may have enhanced its effectiveness in other unexpected ways.

- Villagers had to work outside for long hours in the snow, enduring the extreme cold of Shirakawa-go.

- They might have felt overwhelmed or on the verge of tears due to the hard work in such harsh weather.

- However, they could have persevered, despite their bitterness, knowing that the hearth fire would be burning constantly to warmly welcome them home.

- This fire not only increased the durability of the buildings but also strengthened the resilience of the people, which may be why Shirakawa-go has endured to the present day.

- People in Shirakawa-go might be considered ultimate fire experts, thanks to the centuries of trial and error experienced by their ancestors.

- In Buddhism, a house of discord and constant strife is referred to as a ‘house of fire,’ symbolizing uncontrollable chaos and human vexation.

- People here understand both the risks and benefits of fire, and it might be the only instance in Japanese history where fire has been so successfully controlled.

- However, modern people, who often admire the positive image of the hearth, usually find it regrettable to have introduced one into their homes, as it can cause significant burdens.

- This is because, if we don’t actually need a fire for harsh conditions, introducing an irori might be equivalent to ‘playing with fire.’

- In that case, we should be thankful that the worst outcome was merely a minor burn from our little regret.

6 Gassho-zukuri ground floor (living space)

6.1 Basic Information

- These Gassho buildings primarily have living spaces on the first floor, with the attic above the second floor used for work.

- In a Gassho house with a large family, more than 40 people lived on the ground floor or mezzanine, including multiple generations of family members, relatives, and servant families.

- The spiritual center of the living space was a room with a Buddhist altar, where the entire family held prayer beads and worshipped their ancestors and the founder of the local Buddhism, much like at a church mass

- The room adjacent to the Buddhist altar room served as a bedroom for the patriarch and his wife, a place for family ceremonies, and a reception room for important guests.

- Most of the rooms were boarded up, but these few special rooms had tatami mats, allowing for versatile use by efficiently managing bedding, cushions, and tables.

- The center of daily life was a sunken hearth room, which served as a dining room, living room, and space for sewing and other small tasks, with the hearth providing both heating and light.

- The lattice board hanging above the irori helps spread heat from the hearth to warm the surrounding area and serves as a space for drying wet mantles or smoking skewered river fish, among other uses.

- The order of seating around the irori was generally fixed, with the patriarch at the far end, the women near the kitchen, and the children by the front door, reflecting the patriarchal mindset of the time.

- In the open houses, you can see displays of old lacquerware and other household items used by previous generations. However, be careful not to enter off-limit rooms where the family actually lives.

- The stairs from the first floor to the second and above are narrow and very steep, so caution is required. Generally, descending takes priority, but when crowded, it’s important to take turns and give way.

6.2 Ready to Crack a Smile? Short Stories for You!

Q1 “How many people lived here?”

- Generally, multiple families shared the space, so in some of the larger houses, as many as forty people lived on the ground floor.

- In this narrow, crescent-shaped river basin, there was no land available to divide for new homes, so even when people got married and started their own families, they had no choice but to continue living in their parents’ house or with the eldest son who inherited it.

- Sericulture, which requires continuous care 24 hours a day, also demands a large workforce, so families grew large for practical reasons.

- Although accommodating forty people on one floor was challenging, the families managed well by using a single room for multiple purposes—such as a living room, kitchen, reception room, and bedroom—in the traditional Japanese way.

- For those of us living in the modern world, where privacy is a top priority and individual rooms are the norm, this communal living environment might come as a surprise.

- But here, we may find a hint of a problem-solving approach that could alleviate some of the inevitable harms caused by the freedoms of modern life, even as we celebrate those freedoms.

- For example, since multiple generations of families lived together here, issues like the burden of elderly care by aging children, lonely deaths in apartments, and isolation in private rooms were virtually nonexistent.

- Of course, communal living often requires sacrificing one’s own time and personal space, but there are genuine advantages to such sacrifices for the benefit of others.

- Come to think of it, we often see cases where people end up harming their lives and spirits by failing to manage the many freedoms and ample free time at their disposal.

- Rather, life in Shirakawa-go teaches us that a certain degree of time and space constraint, as experienced here, can be beneficial for the rhythm of life and fostering supportive relationships.

- By the way, a family of forty people is roughly the size of a typical Japanese elementary school class, which sometimes makes me wonder if a gassho-zukuri house, if no longer in use, could serve as a unique space for a school

- The first floor could serve as a classroom for lectures, the hearth room could be used as a campfire area for relaxation, and the spacious attic could be transformed into a gymnasium by removing the partition floors.

- Given the declining birth rate in Japan and the reduced need for elementary school spaces, repurposing such buildings for reskilling programs for the growing number of retired middle-aged and older adults could be a valuable use.

- In a camp-like crash course, participants could raise silkworms to develop service skills in a 24-hour working environment, and some students might even discover new job opportunities in the convenience store industry.

- Daily interactions with a large number of international tourists could boost motivation for language training, as participants become more aware of the need for effective communication skills and language proficiency.

- For many retirees from various companies who may have lost touch with something important due to prolonged recession and fatigue, the school could serve as a reminder of it.

- This is what they routinely did before and after meals in their youth—putting their hands together and expressing gratitude with the word “gassho.”

7 Gassho-style attic (as work space)

7.1 Basic Information

- The upper floors, starting from the second, were efficiently designed and utilized as workspaces, with a mezzanine floor sometimes reserved for servants’ families.

- The attic of a typical Japanese house is small and used only for storage, but here, the attic is spacious, and by dividing it into multiple stories, it maximizes the available workspace.

- The attics here have evolved to enhance the productivity of the highly profitable sericulture work, making it more competitive in the marketplace by applying the same economic principles as modern business.

- Dividing the attic into two to five layers creates more workspace, but it also increases the time spent moving between floors, so the workflow layout was carefully arranged to maximize efficiency.

- For example, young silkworms were raised on the lower floor near the living area because they required constant monitoring and care, while adult silkworms were moved to the upper floor as they required less labor.

- Furthermore, the heat and smoke rising from the hearth on the first floor gradually and naturally adjusted the humidity on each floor as one ascended, allowing different floors to be used with varying humidity levels depending on the stage of silkworm growth.

- Likewise, the heat and smoke rising from below are gradually expelled outward through the thatched roof, staying in the attic to maintain a stable warmth and dryness, creating an ideal environment for raising silkworms, which are sensitive to cold and moisture.

- The gable-end design allows sunlight and air to enter the attic through windows on both sides, creating a bright and well-ventilated space without the need for air conditioning equipment.

- This vast and unique attic, seen only here, can be seen as a premonition of Japan’s later manufacturing and economic success, as it developed the nation’s largest mass production system for sericulture at the time, using a remarkably ingenious low-cost system that wisely leveraged the natural environment.

- You can see the equipment used for raising silkworms, as well as tools for farming and mountain work, offering a glimpse into life in those days. Additionally, some families secretly produced raw materials for gunpowder underground, providing another major source of income.

7.2 Ready to Crack a Smile? Short Stories for You!

Q1 “Was this attic used for storage?”

- This attic is currently used to display old, traditional work tools, but it was primarily used to raise silkworms for the sericulture business.

- Over hundreds of years, it evolved into the large multi-story attics we see today, designed to maximize sales and profitability from sericulture.

- Until the global depression about a hundred years ago, global demand for silk was increasing, and this attic was bustling with activity, raising large numbers of silkworms for what was then modern Japan’s most important export product, earning valuable foreign currency.

- But the global depression and the rise of less expensive synthetic fibers caused the demand for costly silk to fall sharply.

- In addition, unable to compete with the low prices of cocoons from China and other countries with cheaper labor, the silkworms here have almost disappeared from the attic over the past hundred years.

- The displays before us now show the remnants of a time when sericulture was in its heyday, generating enough income to support a large family of several dozen people and maintain this huge attic.

- The many gassho-zukuri buildings in the area, which once numbered nearly 2,000, have now dwindled to about a hundred, as it became difficult to maintain such massive structures.

- However, it’s perhaps a miracle that a few of them are still open to the public, and that so many domestic and foreign visitors continue to visit sites like this today.

- The irony is that Shirakawa-go’s sericulture industry, which lost out in the global silk market, has found new life in the global tourism market, preserving its former glory in a transform.

- In a way, it’s similar to the pyramids in Egypt, which now attract people from around the world to see the structures that once symbolized their former glory.

- Both the attic and the pyramid have an impressive 60-degree slope, capturing people’s attention with their height and mysterious appearance, making everyone wonder, ‘What in the world is this?'”

- When people step inside, they might also notice the similarities. This attic was once a very prosperous kingdom, and they are now witnessing the remnants of its peak—a graveyard of its former glory.

- The owners of this vanished glory are the moths, which were never allowed to exist, as they were destined to be sacrificed for the production of raw silk from their cocoons.

- Since an adult silkworm is referred to as a moth in English, how about promoting this attic with a unique tour titled ‘Japanese-style Pyramid: Mausoleum of Moths: You might even sense the solemn presence of their souls through a Gassho experience!’

- In this experience, you might find yourself naturally putting your hands together in Gassho, just as Japanese people do, to offer a prayer.

8 Gassho-zukuri Attic (As architectural space)

8.1 Basic Information

- In this attic, we can see the determination and strong will embodied in the architecture, designed to survive the harsh natural environment of heavy snowfall, extreme cold, limited land, and scarce food.

- To create more space, this attic uses a truss structure made up of triangles shaped like a mountain, allowing it to stand on its own strength without the need for pillars.

- This method is called gassho-style, but at the apex of the triangle, not visible from below, the two wooden logs are crossed at the top for added strength rather than being perfectly joined, which, in this part, does not fully align with the traditional image of ‘gassho’ in Japan.

- The roof’s angle, about 60 degrees, wasn’t determined by calculations, but rather by years of accumulated experience through trial and error to ensure it could withstand the weight of snow and maximize attic space.

- The windows on both sides were positioned and sized to provide optimal lighting and ventilation at a time before electricity, and to achieve this, a gabled roof, characteristic of the gassho-zukuri style, was adopted..

- The gabled roof also ensured that the attic had no wasted space due to decorative irregularities, allowing the entire rectangular floor to be used as a workspace.

- To increase airflow through both windows, gassho-style houses are oriented with windows facing north and south, taking advantage of the prevailing wind that blows from north to south along the river in this basin.

- Looking out the windows at the other houses all facing the same direction, people sometimes say it feels like a herd of mammoths from the Ice Age or wagons from a Western movie, all moving in the same direction at once.

- The timbers in the attic are bound and assembled with ropes and thin young trees, which are tied loosely rather than rigidly to increase the building’s flexibility and help disperse external forces like strong winds and snow weight.

- To keep building costs low, people here avoided using expensive nails and instead bound the wooden parts with locally sourced young, thin, soft wood, which tends to tighten as it dries, increasing the attic’s strength as it ages, according to locals.

- To maximize the use of heat and smoke rising from the hearth, there is no chimney or large outlet in the attic, allowing the smoke to stay and gradually disperse through the thatched roof.

- The smoke and heat are allowed to linger slowly in the attic, drying and fumigating the interior, protecting the beams and thatch from pests and rot, and increasing the building’s durability.

- The heat slowly released from the gaps in the thatched roofs melts the snow that accumulates in winter, making it easier for the snow to naturally slide off and reducing the workload needed to clear it.

- The soot, or carbon, from the lingering smoke accumulates on the wood inside the attic and on the surfaces of various wooden tools and ornaments over the years, forming a distinct layer that gives them a unique shiny black color known as ‘soot color,’ making these objects valuable as old wood and folk art, sometimes traded at high prices.

- The gassho-zukuri consists of two parts: the first floor and a large triangular attic, but unlike ordinary houses, the two are not attached. Simply put, the attic is surprisingly just placed on top of the first-floor structure.

- Only the tips of the multiple logs running from the top of the roof to the bottom rest on the first floor, with these tips sharpened like pencil points. The contact points between the first floor and the attic are not surfaces or lines, but simply these sharp points.

- Mechanically, this means that even if the attic is heavily shaken by strong winds, the force is dispersed downward through the points of contact, reducing the impact on the first floor.

- Conversely, even if the first floor shakes violently during an earthquake, the same dynamics help reduce damage to the attic, which is why it’s said that historically, gassho-zukuri houses have collapsed less frequently in natural disasters.

- The structural separation between the ground floor and the attic is also tied to the construction method: the ground floor is built by skilled professional carpenters, while the attic is constructed by the villagers of the traditional mutual aid association, ‘Yui.’

- Therefore, while the ground floor is meticulously crafted, from the selection of materials to the finishing touches, the attic is more roughly constructed, with logs left in their natural state and assembled using only ropes or plants. Despite the clear difference in craftsmanship, it is the attic that attracts most tourists.

8.2 Ready to Crack a Smile? Short Stories for You!

Q1 “Why are these roof pillars pointed and wedged?”

- This is called the Komajiri technique, referring to the pointed tip of the main roof pillars in a gassho-zukuri house.

- As you can see, it has a pointed tip that “rides” in a round slot in the thick beam below.

- This pointed tip is an ingenious device designed to receive and disperse the immense pressure from earthquakes, strong winds, and heavy snow that the building endures.

- The tip isn’t completely fixed, but is slightly held in place by a piece of wood that looks like a wedge.

- The purpose is to allow the tip to move freely within a limited range, effectively accommodating and dissipating the sway and force.

- In this way, the pressure on the roof as a whole is prevented from concentrating in certain areas and causing destruction, and both the roof itself and the living space below are protected from damage by the forces of nature.

- This is exactly the kind of wisdom that people in the past developed, and that can be seen in today’s seismic isolation structures.

- Perhaps this structure could even be applied to how we deal with problems in our own lives, especially at work.

- For example, let’s say the upper roof structure is the guest and the lower house structure is me, your local guide.

- If I receive a severe reprimand from the guest – as sharp as the tip of this pillar – due to my inadequacy, I don’t make any excuses or counterarguments.

- Instead, I just silently shake myself a little and wait patiently for their anger to dissipate.

- People can’t stay angry for long, no matter how upset they are, so the tension will eventually cease.

- It’s like using a ”liability isolation structure” instead of a “seismic one”!

- But, you could also say it’s literally an ‘irresponsible structure’ because it’s an idea that simply doesn’t respond to any reprimand.

9 Gassho-zukuri Attic (Remnants of Silkworm Farming)

9.1 Basic Information

- Silkworms, which provided valuable supplementary income to the modest farm earnings, were respectfully called ‘o-kaiko-sama’ (meaning ‘Mr./Mrs. Silkworm’), reflecting the local mentality of gratitude and reverence for everything nature provides.

- Raw silk production can be divided into two main stages: sericulture, where silkworms are raised from eggs until they form cocoons, with tools for this process displayed here, and spinning, where raw silk is extracted from the cocoons.

- During their short 50-day life, silkworms hatch from eggs, feed on mulberry leaves, and mature to form cocoons, the remnants of which visitors can see through displays of panels and various tools.

- Since the quality of silk was greatly affected by the health of silkworms, the attic required 24-hour attention to maintain the right amount of mulberry leaves, temperature, and humidity, as silkworms were extremely sensitive and delicate.

- The silkworm undergoes complete metamorphosis in four stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. After molting four times and forming a cocoon to become a pupa before reaching adulthood, the cocoon is shipped to the next silk manufacturer.

- After the cocoons are dried with steam heat and stored for a certain period, they are unraveled in boiling water and transformed into silk yarn, with each cocoon producing nearly one kilometer of thread.

- Silkworms undergo such dramatic changes in size and form from birth to cocoon-making that they have inspired monster designs in movies. Their weight increases by about 10,000 times, and their silk glands, which produce the silk threads, grow more than 100,000 times.

- Utilizing the silkworms’ natural tendency to climb, two special devices were invented: a net with holes that allows them to climb through, separating their droppings below, and lattice-shaped boards that encourage them to move up into small compartments to spin their cocoons, resulting in neatly aligned cocoons without manual labor.

- Male silkworms produce higher-quality silk and about 20% more than females, but there seems to be no records showing that female silkworms were avoided due to this disadvantage, even during the class-based Samurai period.

- Although the sericulture industry has declined, many people experienced raising silkworms, mainly at school, and vividly remember the sound of silkworms devouring mulberry leaves—much like the sound of light rain or distant waves. Some children even ate their meals quietly after hearing it.

9.2 Ready to Crack a Smile? Short Stories for You!

Q1 “What is this lattice-like board (mabushi)?”

- This net, called a mabushi, is a device made of wood or woven straw, with many small spaces in its frame for silkworms to spin their cocoons.

- Silkworms cannot make cocoons on a flat, empty surface, so they need the mabushi as a scaffold, similar to how humans use scaffolding when building.

- Silkworms have a natural tendency to climb, so when the frame is placed above them, they will climb into the individual small compartments on their own and make their cocoons there.

- However, removing the finished cocoons from their compartments without damaging them is laborious and time-consuming, so a new device was developed

- It’s a new type that rotates vertically, like a Ferris wheel. When placed in the middle of a group of silkworms, they naturally climb up and enter the higher compartments to spin their cocoons.

- The top compartments, filled with silkworms, naturally become heavier, causing them to rotate downward like a Ferris wheel, while the empty compartments at the bottom rotate up to the top.

- By the same logic, the other silkworms fill the higher compartments one by one, causing the same rotation and resulting in a box of cocoons, with all the spaces neatly filled and aligned—without any manual labor.

- That’s a wonderful idea, but am I the only one who somehow sees a similarity to human nature and feels a bit sad?

- Like silkworms, humans also have an upward tendency. When something is placed before us, we feel the urge to climb up and create a comfortable, cocoon-like home to live in.

- But with the weight of the mortgage on the house we’ve built, we may gradually feel like we’re becoming the working poor, and at times, as if we’ve fallen to the bottom of society.

- Additionally, in the comforting, cocoon-like home we worked so hard to build, we may not even be able to live, and someone else might take it away from us,—just like what happens with silkworms.

- We often hear of more and more older husbands at a ripe age going through divorce, blurting out things like this: ‘My comfortable, cocoon-like home is about to be taken away by my tycoon-like wife!

10 Castle Ruins & Observatory

10.1 Basic Information

- On high ground in the south of Shirakawa-go, the castle ruins and observation deck offer a recommended spot for a bird’s-eye view of the entire area, accessible by shuttle bus or on foot.

- Looking down from there, you can see the main street in the middle, with many gassho-zukuri houses beautifully lined up around it, their gable ends—sides with windows—all facing north-south.

- This village is located in a long, narrow, crescent-shaped valley running from north to south, with the wind consistently flowing along the river in the same direction, which improves window ventilation.

- At the same time, the north-south winds can often be so strong and damaging that the gable ends, having the least surface area, are oriented in the same direction to reduce wind damage.

- This orientation also maximizes sunlight and lighting from the windows due to the sun’s east-to-west movement, demonstrating that the entire village was built in a rational manner.

- Unlike many Japanese castles built to demonstrate authority, Ogimachi Castle was constructed on a hill, utilizing the steep slopes on three sides as natural moats and keeping its size minimal for practical purposes, showcasing the same rational mentality seen in gassho-zukuri.

- The castle is one of the smallest, with only a single enclosure, but it overlooks a key transportation route in the area, making it an ideal vantage point for monitoring movement from neighboring regions and evoking the feeling of a sentry in the samurai era.

- There used to be nearly 2,000 gassho-zukuri houses, but most were lost to modernization, including dam construction and redevelopment, leaving only about a hundred today—resembling dwarf houses from a fairy tale or mythical stages that can only be found here.

- On the heights of this observatory, you can enjoy the luxury feeling of photography, souvenir shops, and a restaurant overlooking this spectacular view, and the tranqil feeling of a poet like Homer at the ruins of the castle right next door.

- From this vantage point, you can see that some houses have different roof angles, reflecting the influence of global warming and economic downturn—less snowfall and a shift away from reliance on sericulture—while the unchanged wind flow shaped by the geographic topology remains constant.

10.2 Ready to Crack a Smile? Short Stories for You!

Q1 “Why are we so drawn to this landscape?”

- This high point is a very popular spot in Shirakawa-go and is featured as a must-see location on all tourist sites.

- As you know, it’s not such a high-altitude view, but for some reason, there’s a nostalgic atmosphere that makes us feel at ease.

- For many visitors, it evokes the image of a fairy tale dwarf’s house or a mythical stage watched over by gods.

- Of course, even if the landscape looks peaceful from a distance, the people who live there face various harsh realities.

- For example, gassho-style roofs are costly to maintain, so more houses are being built with conventional roofs.

- In the past, the steep 60-degree roof angle was essential to withstand heavy snowfall, but with decreasing snowfall, gentler angles have become viable.

- There are places in the world where people can visually confirm global warming, and this viewpoint may be one of them.

- By tracking changes in roof angles over time, Shirakawa-go could serve as a watchdog for monitoring global warming.

- Not only the roof angle, the thatch roof can be used as a sensor for summer heat waves, because it is more sensitive to heat than tiled or singled roofs.

- So, we could promote Shirakawa-go, a World Heritage site, as a venue for a global warming summit.

- And if rising sea levels ever submerge Shirakawa-go, at an altitude of about 600 meters, it would almost certainly signal the end of the world.

- We can conduct thorough measurements here right up until that point. Don’t you think that’s a wonderful advertising catchphrase?

11 History of Gassho-Zukuri (Village People’s Story)

11.1 Basic Information

- The existing gassho-zukuri villages are a precious cultural heritage that embody the unique architectural style and mountain lifestyle developed in Japan.

- A pinnacle of functional beauty, gassho-zukuri houses were constructed between the 18th and 20th centuries, with some dating back over 300 years.

- However, in the latter half of the 20th century, rapid changes in lifestyles and industrial structures triggered a mass exodus from rural villages, leading to a dramatic decline in the number of gassho-zukuri houses.

- These abandoned villages generally fall into two categories: those evacuated due to dam construction that submerged the land, and those gradually depopulated due to economic shifts.

- In particular, the decline in sericulture undermined the economic rationale for maintaining the large, high-maintenance gassho-zukuri houses, which had been developed in tandem with the industry.

- It is said that about 90% of the nearly 2,000 houses that once stood in the region have disappeared, and roughly 20% of the 100 villages have been entirely wiped out.

- This loss sparked a sense of urgency and solidarity among local residents, ultimately leading to the adoption of a preservation charter and the designation of the area as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

- Some gassho-zukuri houses—collectively abandoned by villagers—have been relocated and preserved in open-air museums throughout Japan or repurposed as restaurants and tourist facilities in urban areas.

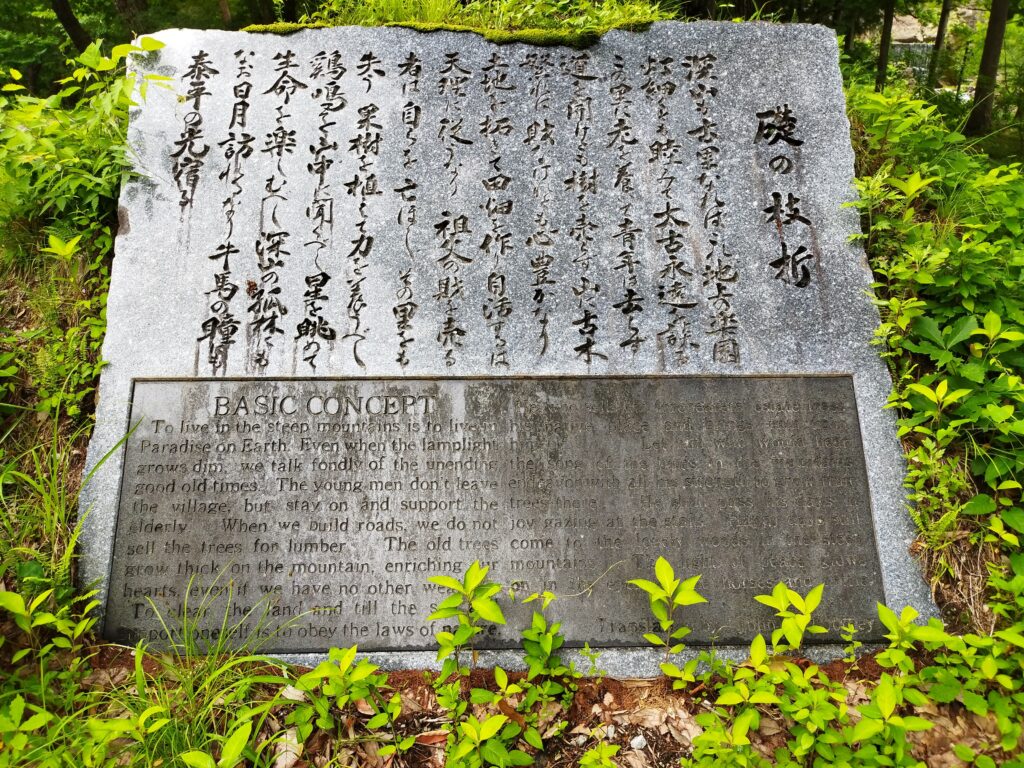

- The Gassho-Zukuri Minka-en, a folklore park opened in 1972, stands as a prime example established to preserve valuable ethnographic heritage.

- Far more than a theme park, it is a vital cultural facility showcasing 25 relocated gassho-zukuri houses, preserving not only their architecture but also the lost ways of life they once embodied.

11.2 Ready to Crack a Smile? Short Stories for You!

Q1 “What is the Gassho-Zukuri Minka-en?”

- The Gassho-Zukuri Minka-en is an open-air museum created over 50 years ago to protect 25 gassho-zukuri houses that were rescued from villages on the brink of disappearing.

- Unlike theme parks built solely for profit, this site serves as a sanctuary—a last refuge—for these traditional homes, which were in sharp decline at the time.

- The goal was to preserve as much of their cultural value as possible.

- The complete loss of dozens of entire villages was a huge shock to the local people.

- The stone monument here, dedicated to the founder, stands like an epitaph, expressing their determination to protect what was vanishing.

- Inside the houses, you’ll find panels showing old newspaper articles about the disappearance of a 700-year-old village and stories of families being separated.

- These displays reveal the hidden, sometimes painful side behind the beautiful exteriors of the gassho-zukuri.

- The interiors also recreate scenes from daily life in those days, including sericulture setups, farming tools, and forestry equipment—things you wouldn’t normally see in public museums.

- Because some visitors mistake the park for just another tourist attraction, I always emphasize as a local guide that this place is quite different.

- It tells the story of people who fought to save as many of these houses as they could.

- To help people understand, I sometimes compare gassho-zukuri houses to extinct dinosaurs.

- They grew large in response to the thriving sericulture industry, but when that industry collapsed, their size made them unsustainable—just like dinosaurs that couldn’t adapt to a changing environment.

- Eventually, I found that the image of a mammoth made even more sense.

- These steep, towering roofs actually resemble mammoths standing proudly.

- But over time, I realized the mammoth metaphor might be risky—some visitors could take it the wrong way, as if I were bragging about Shirakawa-go’s booming tourism.

🔶Thank you so much for reading to the end! If you have any comments or requests, please feel free to reach out to us at the email address provided in the 📧Assistance & Services📞 section.🔶GOLD💎v11a.11a.5a/S1